Summary

Abstract

Zaleplon is a pyrazolopyrimidine hypnotic agent which is indicated for the short term (2 to 4 weeks) management of insomnia.

Zaleplon 5 and 10mg at bedtime (usual recommended doses) significantly reduced sleep latency compared with placebo in clinical trials in nonelderly and elderly patients with insomnia. In general, sleep maintenance (sleep duration and number of awakenings) and sleep quality were not significantly different from placebo with zaleplon 5 and 10 mg/night. Zaleplon 20 mg/night significantly improved sleep latency and duration in nonelderly patients, but effects on number of awakenings were inconsistent and sleep quality generally did not improve. The relative hypnotic efficacy of zaleplon compared with that of triazolam and zolpidem is not yet clearly established.

Tolerance to the hypnotic effects of zaleplon generally did not occur during 5 weeks’ treatment, or during long term treatment (6 or 12 months) according to a small number of studies presented as abstracts.

Zaleplon was well tolerated in clinical trials. The most common event was headache but the incidence was similar to that observed with placebo. Zaleplon 5 and 10mg did not impair psychomotor function or memory even immediately after the dose in studies in volunteers or patients with insomnia. Zaleplon 20mg, however, impaired psychomotor function and memory immediately after the dose but next-day effects were not observed. The psychomotor profile of zaleplon appears to be better than that of comparator agents.

Rebound insomnia was not observed after sudden discontinuation of up to 12 months’ treatment with zaleplon 5 and 10 mg/night and up to 4 weeks’ treatment with zaleplon 20 mg/night. In addition, the potential for withdrawal syndrome with zaleplon appears to be low according to limited data.

In conclusion, zaleplon 5, 10 and 20mg administered at bedtime, or later if patients have difficulty sleeping, is an effective and well tolerated hypnotic agent. There was no evidence of next-day residual effects with the 5 and 10mg dosages, and the incidence of withdrawal effects with zaleplon 5, 10 and 20mg did not differ significantly to that observed with placebo. In addition, tolerance to the effects of zaleplon is unlikely to develop when administered for the recommended treatment period. The comparative efficacy and tolerability of zaleplon with other short acting nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics is difficult to establish. However, on the basis of current efficacy evidence and the lower incidence of residual effects with zaleplon 5 and 10mg relative to comparator agents, this drug represents a useful option in the management of patients with insomnia who have difficulties initiating sleep.

Pharmacodynamic Properties

Zaleplon is a selective agonist at the benzodiazepine ω1 (type 1) receptor subtype. Sleep efficiency significantly improved with zaleplon 5 and 10mg compared with placebo during the first 4 hours, but not over an entire 8-hour period after administration, in a study in healthy volunteers using a phase-advanced sleep model of transient insomnia. In healthy volunteers, no significant residual sedation was observed with zaleplon 5,10 and 20mg compared with placebo during the 4 hours after the dose. In volunteers and patients with insomnia, dosages of ≤10 mg/night had no adverse effects on sleep architecture. Next-day sedation does not occur with zaleplon 5 to 20mg as observed in studies in healthy volunteers and patients with insomnia. In addition, zaleplon 5 and 10mg did not significantly impair psychomotor function or memory as shown predominantly in healthy volunteers but also in patients with insomnia. The 20mg dosage, however, impairs psychomotor function and some parameters of memory immediately after administration but generally no next-day effects were observed. The psychomotor profile of zaleplon 10mg appears to be better than that of zolpidem 10mg, zopiclone 7.5mg and flurazepam 30mg while that of zaleplon 5mg appears to be better than that of zopiclone 7.5mg. The cognitive profile of zaleplon 10mg appears to be significantly better than that of zolpidem 10mg. Although higher than the recommended dose, the psychomotor profile of zaleplon 20mg seems to be better than that of zolpidem 20mg, lorazepam 2mg and flurazepam 30mg and the cognitive profile better than that of zolpidem 20mg and lorazepam 2mg.

Zaleplon (1 to 60mg) did not appear to have any abuse potential in patients with no history of drug abuse. However, the abuse potential of zaleplon (at 2.5 to 7.5 times the therapeutic dose) was similar to that of triazolam (1 to 3 times the therapeutic dose) in volunteers with a history of drug abuse.

Zaleplon does not appear to affect mood in healthy volunteers. Respiratory parameters are not adversely affected by zaleplon 10mg according to a single dose study in patients with insomnia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Pharmacokinetic Properties

The pharmacokinetic parameters of oral single dose zaleplon (5 to 20mg) were assessed in healthy volunteers. The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) increased proportionally with increasing dose. The time to Cmaxis about 1 hour after zaleplon 5, 10 and 20mg, the volume of distribution of zaleplon 10 and 20mg is 276L and the bioavailability of zaleplon 5mg is 30.6%.

The rate, but not the extent, of absorption is increased if zaleplon is administered with or immediately after a high-fat meal.

Concentrations of zaleplon in the breast milk of lactating mothers were lower than those in plasma, and maximum exposure of the infant to zaleplon 10mg during a single feed was estimated to be minimal in this study. However, the manufacturer does not recommend the use of zaleplon during breastfeeding.

Zaleplon undergoes first pass metabolism. It is metabolised to inactive metabolites, primarily by oxidative metabolism, and then predominantly renally eliminated. Clearance parameters are independent of dose; the elimination half-life of zaleplon is short (about 1 hour) and total clearance is 194 to 266 L/h. Zaleplon is absorbed and eliminated more rapidly than zolpidem, and the volume of distribution of zaleplon is higher.

Absorption and elimination parameters of zaleplon are not influenced by age or gender, although a dosage reduction is recommended in elderly patients.

The Cmax and AUC were not influenced by varying degrees of renal impairment but oral clearance of the drug is reduced in patients with hepatic impairment.

A minor metabolic route of zaleplon is via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 subenzyme, thus drugs that strongly inhibit or induce CYP3A4 have the potential to alter plasma concentrations of zaleplon. Coadministration of cimetidine with zaleplon increased plasma concentrations of zaleplon by 85%. Conversely, coadministration of zaleplon 10mg with rifampicin (rifampin) 600mg daily increased the clearance of zaleplon by about 5-fold, thus decreasing Cmax and AUC by 80% resulting in a reduced efficacy. There was no evidence of pharmacokinetic interactions between zaleplon 20mg and imipramine 75mg, thioridazine 50mg or paroxetine 20mg in healthy volunteers, but the psychomotor effects of zaleplon were additive when administered with imipramine and thioridazine. No clinically significant pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic interactions were observed when zaleplon was administered with warfarin, digoxin or ibuprofen to healthy volunteers.

Therapeutic Efficacy

The hypnotic efficacy of zaleplon 5 to 20 mg/night for up to 5 weeks has been evaluated in well designed trials in nonelderly and elderly patients generally with primary insomnia.

Sleep latency (time to sleep onset) was significantly reduced compared with placebo for up to 5 weeks with zaleplon 10 mg/night and for up to 3 weeks with zaleplon 5 mg/night in nonelderly adult patients. In a small sleep laboratory trial, a significant effect was observed with zaleplon 5 and 10 mg/night early (during the first 2 nights), but not later (2 weeks), in the treatment period. Generally, zaleplon 5 and 10 mg/night did not significantly improve sleep maintenance (sleep duration and number of awakenings) or sleep quality compared with placebo in clinical trials.

Zaleplon 20 mg/night significantly improved sleep latency for up to 4 weeks. In addition, sleep duration increased for up to 4 weeks in all but 1 trial. However, no significant improvements were observed in the number of awakenings in 1 large trial but improvements were observed at some time-points in another large trial. Generally, no significant improvements were observed in sleep quality.

The results of a pooled analysis of 3 trials revealed that zaleplon 10 mg/night significantly improved median sleep latency throughout the 4-week study period and increased sleep duration for the first 2 weeks. The higher dosage (20 mg/night) reduced sleep latency for, and increased sleep duration throughout, 4 weeks. In contrast, zaleplon 5 mg/night improved sleep latency during 3 of 4 weeks of treatment but sleep duration was not improved at any time. In general, the number of awakenings was not reduced by any zaleplon dosage.

Subjective assessments of efficacy (patient-based questionnaires) showed better sleep latency (but similar sleep maintenance) results than polysomnography (PSG) data for zaleplon 5, 10 or 20 mg/night in 2 trials using both methods of assessment, but generally similar results were observed in the third trial.

Zaleplon 5 (the recommended dosage in the elderly) and 10 mg/night significantly reduced sleep latency for up to 2 weeks in elderly patients with insomnia, and improvements were significantly greater with zaleplon 10 mg/night than with zolpidem 5 mg/night in 1 comparative trial. Sleep duration and number of awakenings generally did not improve significantly with either zaleplon dosage. Sleep quality significantly improved with zaleplon 5 mg/night during both treatment weeks in 1 trial but at no time-point in the second trial. Zaleplon 10 mg/night significantly improved sleep quality for up to 2 weeks. In comparison, improvements in sleep duration with zolpidem 5 mg/night were significantly greater than with zaleplon 5 mg/night.

In general, the development of tolerance to the hypnotic effects was not observed with zaleplon 10 mg/night in clinical trials of up to 5 weeks’ duration or with zaleplon 5 or 20 mg/night in trials of up to 4 weeks’ duration. Tolerance was also not observed in long term (6- or 12-month) extension studies in nonelderly and elderly patients. However, only a small number of long term studies are available and these were not fully published. Importantly, as with all hypnotics, zaleplon is not indicated for long term use on a nightly basis.

Tolerability

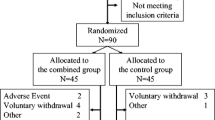

Zaleplon 5, 10 and 20 mg/night was generally well tolerated in both nonelderly and elderly patients with insomnia, and the overall incidence of adverse events and the incidence of individual events was similar or did not differ significantly between zaleplon (5, 10 and 20 mg/night) and placebo in studies of up to 35 days duration. Headache was the most commonly reported event but the incidence of this event was similar to that observed with placebo. Other events occurring with zaleplon 5, 10 or 20 mg/night in nonelderly patients (which were reported in trials by ≥5% of patients in any treatment group and at more than twice the rate versus placebo or in at least 2 groups of patients) included those related to the CNS, gastrointestinal system and respiratory system. Zaleplon 5 or 10 mg/night was generally as well tolerated as triazolam 0.25 mg/night in 1 trial in nonelderly patients, except for nausea which was more frequent with triazolam than with zaleplon 5 mg/night. Comparisons between zaleplon and zolpidem, however, were not conducted in this patient group. The incidence of CNS-related events with zaleplon 5 or 10 mg/night did not differ significantly to that observed with placebo in elderly patients. However, in 1 comparative study, somnolence was significantly more common with zolpidem 5 mg/night than with zaleplon 5 mg/night.

Generally, no clinically significant changes in laboratory, haematological or neurological parameters or vital signs were noted with zaleplon in clinical trials.

Rebound insomnia (worsening from baseline of insomnia symptoms) was not observed after sudden discontinuation of up to 12 months’ treatment with zaleplon 5 and 10 mg/night and up to 4 weeks’ treatment with zaleplon 20 mg/night in nonelderly or elderly patients with insomnia. In comparison, some first-night rebound insomnia was observed with zolpidem 5 mg/night in elderly patients and 10 mg/night in nonelderly patients after discontinuation of 2 or 4 weeks’ treatment based on subjective assessments and with triazolam 0.25 mg/night in nonelderly patients when assessed subjectively, but not by PSG, after discontinuation of 2 weeks’ treatment.

The potential for a withdrawal syndrome appears to be low with zaleplon. The incidence of withdrawal syndrome with zaleplon 5, 10 and 20 mg/night did not differ significantly to that observed with placebo after discontinuation of 4 weeks’ treatment, and was relatively low (<4.5%) with zaleplon 10 mg/night in a non-comparative long term (12 months) trial.

Dosage and Administration

Zaleplon is indicated for use in patients with insomnia who have difficulties initiating sleep. The usual recommended dosage of zaleplon is 10 mg/night; a 5 mg/night dosage is recommended in the elderly, in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment and in patients taking concomitant cimetidine. The maximum recommended dosage is 20 mg/night in the US (recommended for the occasional nonresponsive patient) and 10 mg/night in Europe. Zaleplon should not be used in patients with severe hepatic impairment. The recommended duration of treatment is ≤2 (Europe) or ≤4 (US) weeks.

Coadministration of alcohol and other centrally acting drugs may potentiate the sedative effects of zaleplon.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wagner J, Wagner ML, Hening WA. Beyond benzodiazepines: alternative pharmacologic agents for the treatment of insomnia. Ann Pharmacother 1998 Jun; 32: 680–91

Freeman HL. Is there a need for a pure hypnotic? Approaches to the co-diagnosis of insomnia and anxiety. J Drug Dev Clin Pract 1996 Jan; 7: 289–302

Hajak G, Rodenbeck A. Clinical management of patients with insomnia: the role of zopiclone. PharmacoEconomics 1996; 10 Suppl. 1: 29–38

Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation survey. Sleep 1999 Sep; 22 Suppl. 2: S347–53

Kupfer DJ, Reynolds III CF. Management of insomnia. N Engl J Med 1997 Jan 30; 336: 341–6

Noble S, Langtry HD, Lamb HM. Zopiclone: an update of its pharmacology, clinical efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs 1998 Feb; 55: 277–302

Parino L, Boselli M, Spaggiari MC, et al. Multidrug comparison (lorazepam, triazolam, zolpidem, and zopiclone) in situational insomnia: polysomnographic analysis by means of cyclic alternating pattern. Clin Neuropharmacol 1997 Jun; 20(3): 253–63

Parrino L, Terzano MG. Polysomnographic effects of hypnotic drugs: a review. Psychopharmacology 1996 Jul; 126: 1–16

Gallopin T, Fort P, Eggermann E, et al. Identification of sleep promoting neurons in vitro. Nature 2000 Apr; 404: 992–5

Zammit GK. Redefining a good night’s sleep. In: Roberts WO, editor. Insomnia: treatment options for the 21 st century. Minneapolis (MN): McGraw-Hill Healthcare Information Group, 2000: 33–40

Becker PM, Jamieson AO, Brown WD. Insomnia: use of a ‘decision tree’ to assess and treat. Postgrad Med 1993 Jan; 93(1): 66–85

Roth T, Ancoli-Israel S. Daytime consequences and correlates of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation survey II. Sleep 1999 May; 22 Suppl. 2: S354–8

Roth T. Overview of insomnia for the primary care physician. In: Roberts WO, editor. Insomnia: treatment options for the 21st century. Minneapolis (MN): McGraw-Hill Healthcare Information Group, 2000: 5–13

Wagner ML. Zaleplon. CNS Drugs 1999 May; 11: 393–4

Hurst M, Noble S. Zaleplon. CNS Drugs 1999 May; 11: 387–92

Dämgen K, Lüddens H. Zaleplon displays selectivity to recombinant GABAA receptors different from zolpidem, zopiclone and benzodiazepines. Neurosci Res Commun 1999; 25(3): 139–48

Beer B, Clody DE, Mangano R, et al. A review of the preclinical development of zaleplon, a novel non-benzodiazepine hypnotic for the treatment of insomnia. CNS Drug Rev 1997; 3(3): 207–24

Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, von-Moltke LL, et al. Comparative kinetics and dynamics of zaleplon, zolpidem, and placebo. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1998 Nov; 64: 553–61

Danjou P, Paty I, Fruncillo R, et al. A comparison of the residual effects of zaleplon and zolpidem following administration 5 to 2 h before awakening. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999 Sep; 48: 367–74

Rush CR, Frey JM, Griffiths RR. Zaleplon and triazolam in humans: acute behavioral effects and abuse potential. Psychopharmacology 1999 Jul; 145: 39–51

Vermeeren A, Danjou PE, O’Hanlon JF. Residual effects of evening and middle-of-the-night administration of zaleplon 10 and 20 mg on memory and actual driving performance. Hum Psychopharm 1998; 13: S98–107

Dietrich B, Emilien G, Salinas E. Efficacy of zaleplon on sleep and daytime performance in a phase-advanced sleep model. Wyeth-Ayerst, 1998 (Data on file)

Beer B, Ieni JR, Wu W-H, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of single escalating doses of CL 284,846, a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic. J Clin Pharmacol 1994; 34: 335–44

Allen D, Curran HV, Lader M. The effects of single doses of CL284,846, lorazepam, and placebo on psychomotor function and memory function in normal male volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 45: 313–20

Dietrich B, Emilien G, Salinas E. Zaleplon does not produce residual sedation in a phase-advance model of transient insomnia [abstract]. J Sleep Res 1998 Sep; 7 Suppl. 2: 67

Scharf MB. Evaluation of next-day functioning and residual sedation in healthy subjects: zaleplon vs. flurazepam. In: Roberts WO, editor. Insomnia: treatment options for the 21 st century. Minneapolis (MN): McGraw-Hill Healthcare Information Group, 2000: 25–32

Troy SM, Lucki I, Unruh MA, et al. Comparison of the effects of zaleplon, zolpidem and triazolam on memory, learning, and psychomotor performance. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20(3): 328–37

Walsh JK, Fry J, Erwin CW, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of 14-day administration of zaleplon 5mg and 10mg for the treatment of primary insomnia. Clin Drug Invest 1998; 16(5): 347–54

Cluydts R. A 28-night evaluation of the efficacy, next-day effects and withdrawal potential of zaleplon and zolpidem in outpatients with primary insomnia. In: Roberts WO, editor. Insomnia: treatment options for the 21 st century. Minneapolis (MN): McGraw-Hill Healthcare Information Group, 2000: 14–24

Walsh JK, Pollak CP, Scharf MB, et al. Lack of residual sedation following middle-of-the-night zaleplon administration in sleep maintenance insomnia. Clin Neuropharmacol 2000; 23(1): 17–21

Walsh JK, Vogel GW, Scharf M, et al. A five week, polysomnographic assessment of zaleplon 10 mg for the treatment of primary insomnia. Sleep Med 2000; 1: 41–9

Sanger DJ. The effects of new hypnotic drugs in rats trained to discriminate ethanol. Behav Pharmacol 1997 Aug; 8: 287–92

Vanover KE, Barrett JE. Evaluation of the discriminative stimulus effects of the novel sedative-hypnotic CL 284,846. Psychopharmacology 1994; 115: 289–96

Sanger DJ. Behavioural effects of novel benzodiazepine (ω) receptor agonists and partial agonists: increases in punished responding and antagonism of the pentylenetetrazole cue. Behav Pharmacol 1995; 6: 116–26

Sanger DJ, Morel E, Perrault G. Comparison of the pharmacological profiles of the hypnotic drugs, zaleplon and zolpidem. Eur J Pharmacol 1996; 313: 35–42

Scharf M. Zaleplon: no next-day residual sedation or psychomotor impairment. Acompilation of recent zaleplon abstracts and posters, Wyeth, 1999 (Data on file)

The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products European Public Assessment Report (EPAR): Sonata. Report number: CPMP/897/99, 1999

Darwish M. The relationship between the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zaleplon [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999 Sep; 9 Suppl. 5: S361

George CFP, Series F, Kryger MH, et al. Safety and efficacy of zaleplon versus zolpidem in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and insomnia [abstract]. Sleep 1999; 22 Suppl.: S320

Drover DR, Lemmens HJM, Naidu S, et al. The comparative pharmacokinetics of zaleplon and zolpidem [abstract]. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999 Feb; 65: 168

Rosen AS, Fournic P, Darwish M, et al. Zaleplon pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability. Biopharm Drug Dispos 1999 Apr; 20: 171–5

Darwish M. The effects of age and gender on the pharmacokinetics of zaleplon [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999 Sep; 9 Suppl. 5: S360

Darwish M, Martin PT, Cevallos WH, et al. Rapid disappearance of zaleplon from breast milk after oral administration to lactating women. J Clin Pharmacol 1999 Jul; 39: 670–4

Wickland C, Patat A. The pharmacokinetics and safety of zaleplon in patients with renal impairment [abstract]. Sleep Research 1999; 2 Suppl. 1: 172

Wickland C, Patat A. The safety and pharmacokinetics of zaleplon in hepatically impaired patients [abstract]. Sleep Research 1999; 2 Suppl. 1: 171

Lee W-H, Amorusi P, DeMaio W, et al. Metabolic disposition of radiolabeled zaleplon (CL-284846) in healthy male volunteers. Wyeth-Ayerst, 1998 (Data on file)

Wyeth-Ayerst. Sonata prescribing information. USA, 1999

Lundbeck Ltd. Sonata summary of product characteristics. UK, 2000

Darwish M. Analysis of potential drug interactions with zaleplon. Acompilation of recent zaleplon abstracts and posters, Wyeth, 1999 (Data on file)

Darwish M. Overview of drug-interaction studies with zaleplon. Sleep 1999; 22 Suppl.: S280

Darwish M. Analysis of potential drug interactions with zaleplon. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999 Sep; 47: S62

Sanchez Garcia P, Carcas A, Zapater P, et al. Absence of an interaction between ibuprofen and zaleplon. Am J Health System Pharm 2000 Jun; 57: 1137–41

Darwish M. Minimal interactions between zaleplon and three psychotropic agents. Wyeth-Ayrest, 1999 (Data on file)

Hetta J, Broman J-E, Darwish M, et al. Psychomotor effects of zaleplon and thioridazine coadministration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol In press

Elie R, Rüther E, Farr I, et al. Sleep latency is shortened during 4 weeks of treatment with zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic. J Clin Psychiatry 1999 Aug; 60: 536–44

Dietrich B, Farr I. Zaleplon: dose response evaluation in primary insomnia [abstract]. Sleep Research 1995; 24A: 116

Ancoli-Israel S, Walsh JK, Mangano RM, et al. Zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, effectively treats insomnia in elderly patients without causing rebound effects. J Clin Psychiatry 1999 Aug; 1(4): 114–20

Fry J, Scharf M, Mangano R, et al. Zaleplon improves sleep without producing rebound effects in outpatients with insomnia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 15: 141–52

Hedner J, Yaeche R, Emilien G, et al. Zaleplon shortens subjective sleep latency and improves subjective sleep quality in elderly patients with insomnia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. In press

Elie R, Davignon M, Emilien G, et al. Zaleplon decreases sleep latency in outpatients without producing rebound insomnia after 4 weeks of treatment [abstract]. J Sleep Res 1998; 7 Suppl. 2: 76

Hedner J, Emilien G, Salinas E. Improvement in sleep latency and sleep quality with zaleplon in elderly patients with primary insomnia [abstract]. J Sleep Res 1998; 7 Suppl. 2: 115

Elie R. Zaleplon is effective in reducing time to sleep onset. Wyeth-Ayerst, 1999 (Data on file)

Elie R. Zaleplon is effective in reducing time to sleep onset [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9 Suppl. 5: S361

Holm KJ, Goa KL. Zolpidem: an update of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs 2000 Apr; 59(4): 865–89

Hedner J, Mangano R. Zaleplon provides safe long-term treatment of insomnia in the elderly [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999 Sep; 9 Suppl. 5: S362

Scharf M. The safety of long-term treatment of insomnia with zaleplon [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999 Sep; 9 Suppl. 5: S360

Hedner J, Darwish M, Mangano RM. Zaleplon provides safe and long-term treatment of insomnia in the elderly. Wyeth-Ayrest (UK), 1999 (Data on file)

Mangano RM. Zaleplon: a safe and effective hypnotic. A compilation of recent zaleplon abstracts and posters, Wyeth, 1999, (Data on file)

Scharf MB. The safety and long-term treatment of insomnia with zaleplon. Wyeth-Ayrest (UK), 1999 (Data on file)

Walsh JK, Engelhardt CL. The direct economic costs of insomnia in the United States for 1995. Sleep 1999 May; 22 Suppl. 2: S386–393

Fraser AD. Use and abuse of the benzodiazepines. Ther Drug Monit 1998 Oct; 20: 481–9

Woodward M. Hypnosedatives in the elderly: a guide to appropriate use. CNS Drugs 1999 Apr; 11: 263–79

Lader M. Withdrawal reactions after stopping hypnotics in patients with insomnia. CNS Drugs 1998 Dec; 10: 425–40

Rhûne-Poulenc Rorer Limited. Zimovane prescribing information. ABPI compendium of data sheets and summaries of product characteristics, Datapharm Publications Limited, 1998–1999

Lorex Synthelabo. Stilnoct prescribing information. ABPI compendium of data sheets and summaries of product characteristics, Datapharm Publications Limited, 1998–1999

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dooley, M., Plosker, G.L. Zaleplon. Drugs 60, 413–445 (2000). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200060020-00014

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200060020-00014